What is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)?

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is a condition where the heart muscle becomes thickened. Although HCM is a relatively rare heart disease, it is the commonest of the cardiomyopathies, affecting 1 in every 500 people.

Traditionally, the term HCM was used for disease caused by abnormalities in genes which make the proteins responsible for contraction of the heart, ‘the sarcomere’. More recently the definition of HCM has been broadened to include a number of other conditions that result in thickened heart muscle.

It is a disease that can affect both men and women of any ethnic background. Excessive muscle thickening tends to develop in puberty or early adulthood or can sometimes develop very late in life. Rarely, it may even begin before birth when the baby’s heart is developing and cause problems in childhood.

In a healthy adult heart, the muscle fibres are arranged in an organised fashion and the thickness of the heart’s wall remains normal. In HCM, however, the heart muscle becomes excessively thick and the fibres are arranged haphazardly making the heart vulnerable to life threatening heart rhythms (ventricular fibrillation/ventricular tachycardia). The thickening may also reduce the efficiency of the heart’s pumping action or even lead to the blockage or ‘obstruction’ of blood leaving the main pumping chamber of the heart. This can result in the symptoms described below. Diagnosing HCM may pose a significant challenge since the heart muscle may also thicken in individuals who have high blood pressure or who participate in prolonged athletic training.

Symptoms

If you have HCM you may never experience any symptoms. If you do suffer symptoms they can vary from person to person and may begin in infancy, childhood, middle or elderly life. No particular symptom or complaint is unique to HCM sufferers.

The most common symptoms are:

- shortness of breath, usually brought on by physical exertion

- chest pains, usually brought on by physical exertion

- palpitations, a rapid and/or irregular heart beat

- light-headedness, blackouts

If you suffer from any of these symptoms it does not mean that you necessarily have HCM but if you visit your GP he/she may suggest that you have some tests; or refer you to a cardiologist.

How is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy diagnosed?

Diagnosis involves you having an ECG and an ultrasound scan of the heart known as an echocardiogram (ECHO). Most people with HCM have an abnormal ECG and often the ECG may become abnormal long before thickening of the heart can be seen on an ECHO. If HCM is suspected, an exercise ECG and a Holter monitor will be required. In some cases further imaging of the heart may be necessary using a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

Genetic testing can identify carriers of the HCM gene. Unfortunately, this form of testing is limited at the moment, as 3 – 4 in every 10 people who are known to have HCM do not have mutations of the genes known to be associated with HCM. An additional problem is that many families who do have the mutations appear to have a specific change to the DNA code which is not found in other families (known as a ‘private’ mutation). This sometimes makes it difficult to decide whether a mutation is causing the disease or not. Things are further complicated because people with the same mutation can have different effects. However, if a well known mutation is identified, genetic testing can be used to confirm the diagnosis, or offered to the family to screen for the condition.

What treatment is available?

There is no cure at present for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Treatment is aimed at preventing complications and improving symptoms. If your tests prove positive your specialist will advise you on your lifestyle. You will probably be advised not to participate in competitive sport and strenuous activities. You will also be advised to keep well hydrated, particularly when exercising or in hot weather. For many people the condition should not significantly interfere with their lifestyle.

Drugs are given when a patient has symptoms. A variety of drugs are used in the treatment of HCM and the choice will vary from patient to patient. However, if you have severe symptoms due to blockage or ‘obstruction’ of blood flow, and you do not improve on tablets, surgical myectomy or alcohol septal ablation may be suggested (see below). These can be successful in the relief of symptoms due to obstruction by removing or damaging a portion of the thickened muscle.

There are other forms of treatment, which are occasionally recommended:

- Electrical cardioversion may be used to treat atrial fibrillation (irregular heart beat), which is quite common.

- A pacemaker may be fitted if your heart’s normal electric signal fails.

- An Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator (ICD) may be fitted for you if you have suffered a previous cardiac arrest or a dangerous ventricular arrhythmia. An ICD will also be considered even if you have not had these symptoms but have other risk factors during your assessment.

In a small number of patients the heart pump weakens eventually and symptoms of heart failure (breathlessness and ankle swelling) will require treatment (described in dilated cardiomyopathy).

Non-pharmacological treatment of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

A subset of patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (approximately 25%) can develop substantial increase in their heart muscle thickness, which can cause obstruction for the blood to be pumped out the heart. This can lead to development of significant symptoms such as chest pain and/or difficulty in breathing.

Such individuals can be treated with drugs such as beta-blockers. However in some patients, symptoms continue to persist in spite of treatment with drugs. There are two other forms of treatments available for such patients to improve their symptoms.

- Surgical myomectomy. This is a major operation which involves opening of the chest and taking out a ‘chunk’ of the heart muscle that is causing obstruction. Since this is a major operation, it comes with some risks such as hazardous effects of general anaesthesia, risk of damaging other areas of the heart, etc.

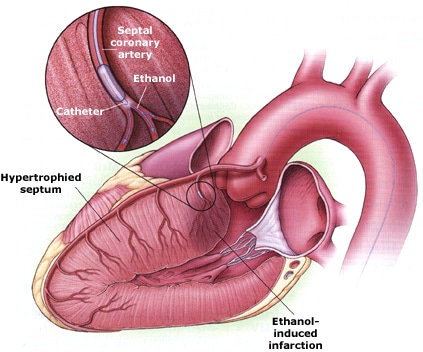

- Alcohol septal ablation. This is a relatively less invasive procedure which is done under local anaesthesia and sedation and is often used in patients that cannot undergo a myomectomy. In this procedure a small amount of alcohol is injected into the blood vessels supplying thickened areas of the heart muscle in an attempt to cause death of that particular area. This is because alcohol is extremely toxic to the heart muscles. The dead muscles are then replaced by a scar tissue (see the figures below). These changes result in reduction in bulk of the muscle, which in turn relieves obstruction. This also leads to a relatively bigger chamber (left ventricle) which aids the heart to receive larger amounts of blood. The procedure is performed like an angiogram where the operator gains access to the blood vessels in the heart via groin or via wrist. However this procedure also carries some risk such as damage to the electrical system of the heart which might result in the need for a pacemaker. In some cases, the wrong areas of heart muscle might be destroyed causing some unwanted effects. However, due to minimal invasive nature of the procedure, it is gaining more popularity than the traditional surgical operation.

What should you do if you are diagnosed with Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy?

If your tests prove positive your specialist will advise you on your lifestyle and you will probably be advised not to participate in continuous strenuous activities – e.g. competitive sports. Most of the time the condition should not significantly interfere with your lifestyle and can be controlled by drugs if necessary.

In a small proportion of patients, after appropriate risk stratification, an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) may be recommended. You will be guided by your specialist in this regard.

It will be necessary for you to have at least annual check-ups. However, the severity of the disease varies from person to person and even if you have been diagnosed with HCM you may not necessarily present any symptoms and can live a normal life. Since the disease runs in families, all immediate blood relatives of affected patients have to be screened with an ECG and an ECHO.

It is recommended that when HCM is identified in a family member, those first degree blood relatives where the condition is NOT identified should return for repeat testing yearly until the age of 21, then every 5 years until the age of 60.

We are grateful to Camilla Wheeler of the Community Education Department, Yorkshire Television, for permission to reproduce information on hypertrophic cardiomyopathy from a factsheet produced to coincide with a “3-D” programme on Sudden Death Syndrome, first transmitted in April 1995