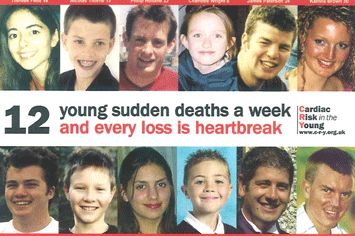

Sudden Death Syndrome steals a dozen young British lives a week. Samantha Laurie feels the pulse of a pioneering new programme putting young hearts to the test.

It was eight years ago, on a wintry Wednesday morning, when Rob Thorne received the call every parent dreads – his 13-year-old son, Nicholas, had collapsed in the school playground whilst kicking a football around with his mates.

By the time Rob and his wife had left their home in the Surrey village of Smallfield and reached the school, Nicholas had been taken by ambulance to East Surrey hospital. In the playground two older girls had administered basic CPR and paramedics shocked his heart, but he never regained consciousness. Over the next two days his heart arrested 16 times and he died on the Friday afternoon.

“We had to leave him at the hospital and get a train home. We sat in silence listening to a couple arguing over a seat, wondering how it was possible that the world was still turning yet ours was devastated,” recalls Rob.

Nicholas had an undiagnosed arrhythmic heart condition – an instability in the wiring mechanism of the heart that caused it continually to stop and restart. There were no symptoms – except perhaps the breathlessness that had been diagnosed as asthma and no family history. Later, when the rest of the family was tested, no one had any sign of heart abnormality.

Yet the condition might well have been picked up by routine cardiac screening. It could have been treated with a defibrillator. Instead, Nicholas became one of the 12 seemingly fit and healthy young people a week in the UK who die from Sudden Death Syndrome – the umbrella term for various undiagnosed and largely symptomless congenital heart defects relating to the electrical circuitry or muscle of the heart.

This month, Epsom charity Cardiac Risk in the Young (CRY) is launching a free screening programme for 14-year-olds. The 10-minute tests, at St George’s Hospital in Tooting, will be offered to every child in the region born in 1995, as 14 is the optimum age for screening – post-puberty, but before the high risk years of 16-22. Participants will be rescreened in 2015, and the overall results will form the first comprehensive data in the world on the prevalence of heart conditions in a single age group.

It’s another milestone in the 15-year battle of charity founder Alison Cox to force cardiac death up the national agenda.

“When someone dies of a heart flaw, we tend to see it as just a tragic stroke of bad luck,” she says. “But there are 12 people dying of this every week – 12 families who could have been spared if we had a national screening programme. Screening identifies one young person in 300 as having a potentially fatal flaw that is treatable, if not curable. Three per average size school.”

Alison herself became involved when her 18-year-old son came home with a heart condition from a sports scholarship in the USA. The US testing programme saved his life, but it is Italy that is the ultimate model for screening. Since 1982, everyone involved in organised sport – amateur or professional – has been screened, and sudden cardiovascular death has fallen by 89%.

For the under 35s, sport is a key trigger in cardiac death. Many of the conditions are linked to adrenalin rushes, and often it is the fittest member of the family that is affected. Ralph Murwill, a healthy physiotherapist brought up in Kingston, died two years ago at 28 as he crossed the finish line of a half-marathon. Doctors believe that, as his heart went into recovery from the run, it switched on a rare electrical fault; a condition known as brugada. Yet at post-mortem his heart was perfect.

“There’s nothing more unnatural that to lose your child to natural causes,” says Alison. “Yet that is all many families are often left with, as these conditions are often undetectable once the heat has stopped beating.”

Funding from another Surrey family, the Hunters, who lost father and son to the same condition, has enabled CRY to set up one of the world’s leading cardiac pathology centres at the Royal Brompton Hospital, giving families access to faster and more specialised diagnoses.

So far, however, most screening in the UK has centred on professional athletes. In football, the deaths of Motherwell captain Phil O’Donnell and Cameroon midfielder Marc-Vivien Foe galvanised the FA, but amateur bodies have yet to catch on. Now Alison hopes that the St George’s programme will provide the model for a national scheme. Meanwhile, CRY offers subsidised testing (£35) to over 10,000 young people a year at specialist clinics, or via mobile screening units visiting sports clubs and schools.

Raising awareness of symptoms is also a top priority. Only 20% of young people with abnormalities exhibit them – chest pain, breathlessness, dizziness, fainting fits, palpitations – and these are often disregarded in healthy teenagers. Family history is also crucial: unexplained deaths, such as drowning by good swimmers should be taken into careful consideration.

Some will object that screenings fail to pick up every condition, or that false positives could wreck sporting careers. But for the Thorne family, a screening would have been a godsend. Three months ago they celebrated Nicholas’s 21st birthday – at his graveside.

“This article originally appeared in Samantha Laurie’s Child’s Play column in the Sheengate Publishing series of titles, incorporating The Richmond, Elmbridge Lifestyle, Guildford and Surrey Downs Magazines.”